|

Rotten Library > Culture > The Prisoner

The Prisoner The poignant thing about innocence is that you can only lose it once.

The poignant thing about innocence is that you can only lose it once. Starting in 1967, millions of viewers lost their innocence to a British television production known as The Prisoner. Unlike anything previously seen in mainstream television or film, The Prisoner permanently changed the rules of engagement between makers of entertainment and consumers of entertainment. Before The Prisoner, you could settle down in front of the TV secure in the knowledge that you would be served up a tasty and reasonably satisfying bit of fluff with a beginning, a middle and an end. While the quality might vary, depending on the skills of the writers, directors and actors involved, you knew for certain that everyone was trying their best to give you what you wanted. Into that complacency, The Prisoner dropped like an atomic bomb. Over the course of 17 one-hour episodes, The Prisoner toyed with its viewers like a particularly sadistic cat with an especially clueless mouse. The show trotted out its tantalizing enigmas with the usual straight-faced sobriety, challenging viewers to figure out the Big Questions before the big finale in which all would be revealed. The viewers took up that challenge with childlike enthusiasm, little dreaming what Daddy had in store for them. The Prisoner was the brainchild of Patrick McGoohan, who had become familiar to British and U.S. viewers as John Drake, the stalwart protagonist of Danger Man (aka Secret Agent).

With its brisk action and memorable theme song (Secret Agent Man by Johnny Rivers), Danger Man was extremely popular, but McGoohan was getting bored with its black-and-white morality tales and formulaic plots. McGoohan was approached to play James Bond, but he declined, fatefully suggesting Sean Connery for the role instead. ITV, the production company behind Danger Man was keen to pick the series up for another season, but McGoohan made a counterproposal. He had an idea for a new series in the spy genre, a series he would produce, write and direct. The concept was easy enough to comprehend at this stage. A secret agent resigns from his employer in the midst of the Cold War and is subsequently kidnapped by forces unknown. His captors take him to a strange town simply known as The Village. Located on a remote island, The Village seems like a quaint anachronism of a British resort town, but every resident is subjected to constant surveillance by hidden cameras and spies planted among the population.

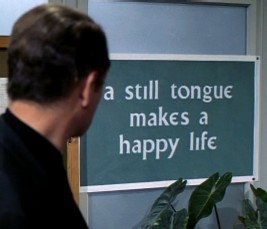

While the idea itself was fairly simple, its execution was unbelievably complex. Everyone in the Village is given numbers. Names are never used, a rule observed so assiduously that the audience never even learns the name of the main character, played by McGoohan. Characters were assigned numbers. The Prisoner was told that he was No. 6, but he refused to accept the designation, defiantly shouting, "I am not a number, I am a free man!" The Village was a trippy place. Security was provided by Rover, a menacing white blob portrayed by a weather balloon with a penchant for smothering wayward prisoners. Penny-farthing bicycles were everywhere in the Village, inexplicably. The technology was pure science-fiction for its day. Although the cordless phones, tape-spooling computers, lava lamps and miniature cameras are painfully dated today, they were quite the space-age artifacts at the time. Fortunately, the surreal nature of the Village mostly masks the show's 1960s sensibilities for modern viewers. The Village was run on a day-to-day basis by No. 2. Each week, there was a new No. 2, played by a different actor, with little explanation offered. No. 2 had many responsibilities, but one towered over all the rest... Find out why No. 6 resigned. Each week brought new and elaborate mind games designed either to extract this ultimate secret, or simply to break the Prisoner's spirit. Each week, the effort failed, but it was a close call sometimes.

Rather than simply wire electrodes to the Prisoner's genitals, each No. 2 presented a new and innovative scheme to unlock the Prisoner's brain. Ploys ranged from hallucinogen-induced alternate realities to fixed elections to staged escapes to femme fatales to identical twins to brain surgery. Some were so bizarre they can barely be related, others were elegant in their simplicity. Almost every episode was an allegory about the inherent struggle of maintaining individuality while living in society. Sometimes the struggle was buried in dense layers of symbolism, as in "The Dance of the Dead." Other times, the theme was profoundly in your face. In the episode titled "Free for All," the Prisoner is invited to run for the position of No. 2 in a scathing indictment of the democratic process and the media. An interview with the candidate goes to press before it's even finished. "Less work and more play" is a platform plank. Under the influence of brainwashing, the Prisoner spouts meaningless gibberish to cheering crowds.

McGoohan wrote and directed several of the episodes, including the final two episodes, which represent the culmination of the series. Other collaborators included series co-creator George Markstein (who left the show in a huff when he found out what McGoohan had planned for the finale), David Tomblin, Anthony Skene and Vincent Tilsley. It's probably best not to discuss the plot of the final two episodes of The Prisoner, which are best experienced without spoilers. But it's safe to say that the final episode was easily the most controversial hour of television in history. While many viewers were still uncertain about the answers to their questions, they had fairly clear expectations about what constituted answers, and they felt entitled to receive some. You can mount an argument about whether The Prisoner answered any or all of its many questions in the final episode, but it definitely wasn't like anything that had been seen on television before. Angry calls poured into the switchboards at ITV for hours after the program ended.

Whatever one chooses to take from the final episode of The Prisoner, the series was a tremendous influence on movies and television that came after it. Its cool paranoia, intelligent characters and razor-sharp dialogue directly influenced dozens of concepts that came after, including The X-Files and Twin Peaks. In addition to stylistic and thematic influences, The Prisoner raised the possibility of a new kind of art disguised as entertainment. Just two years later, 2001: A Space Odyssey would offer a similar kind of conclusion, a climax deeply masked in symbolism and considered impenetrable by some. The lack of closure in the final episode of The Prisoner opened the door to Surrealism and abstraction in television, a medium that had previously been distinguished mostly by the depressing sameness of its fare. McGoohan offered up the visual equivalent of a Salvador Dali painting: difficult, disturbing and nonlinear.

When Homer's Web site accidentally uncovers a government conspiracy, he's kidnapped and taken to "The Island" where he's given the number 5. "In your face, Number Six!" he crows. In the end, the whole Simpson clan is taken to The Island, apparently for life. As Marge observes, "Once you get used to the constant druggings this place really isn't so bad." Rumors of a Prisoner movie have circulated for years, but the project never seems to get off the ground. If it happens, it will almost certainly suck, no matter how skillfully it is crafted. Because, don't forget, the poignant thing about innocence is that you can only lose it once.

|

Danger Man was a cross between The Saint and Mission Impossible, a fairly straightforward spy show in which Drake traveled the globe, performing acts of espionage and derring-do.

Danger Man was a cross between The Saint and Mission Impossible, a fairly straightforward spy show in which Drake traveled the globe, performing acts of espionage and derring-do.  McGoohan's character is of particular interest to his captors. They wanted to know why he resigned, and they played endless mind games with their prisoner in an effort to get him to talk.

McGoohan's character is of particular interest to his captors. They wanted to know why he resigned, and they played endless mind games with their prisoner in an effort to get him to talk. Viewers entered the series as clueless about the reasons for the Prisoner's resignation as his captors. Several other major questions immediately presented themselves: Which side runs the Village? Is it "us" or "them"? What do they really want? And perhaps most important, if No. 2 is the administrator of the Village, who is No. 1?

Viewers entered the series as clueless about the reasons for the Prisoner's resignation as his captors. Several other major questions immediately presented themselves: Which side runs the Village? Is it "us" or "them"? What do they really want? And perhaps most important, if No. 2 is the administrator of the Village, who is No. 1?  The episode "Living in Harmony" featured a typical Prisoner episode, only set in the American Old West. The Prisoner is forced to serve as the sheriff of a small town called Harmony. The Sheriff refuses to carry a gun, which was considered a loaded political comment during the height of the

The episode "Living in Harmony" featured a typical Prisoner episode, only set in the American Old West. The Prisoner is forced to serve as the sheriff of a small town called Harmony. The Sheriff refuses to carry a gun, which was considered a loaded political comment during the height of the  Ten years later, an interviewer asked McGoohan the question on everyone's mind. What was he thinking? "I wanted to have controversy, argument, fights, discussions, people in anger waving fists in my face saying, 'How dare you? Why don't you do more (shows) that we can understand?' I was delighted with that reaction. I think it's a very good one; that was the intention of the exercise."

Ten years later, an interviewer asked McGoohan the question on everyone's mind. What was he thinking? "I wanted to have controversy, argument, fights, discussions, people in anger waving fists in my face saying, 'How dare you? Why don't you do more (shows) that we can understand?' I was delighted with that reaction. I think it's a very good one; that was the intention of the exercise." A Prisoner comic book sequel was published in the late 1990s, and a handful of books and parodies occasionally pop up. In a 2000 episode of

A Prisoner comic book sequel was published in the late 1990s, and a handful of books and parodies occasionally pop up. In a 2000 episode of